Memo to Screenwriters #2: Like E.L. James, You Can Change the Game

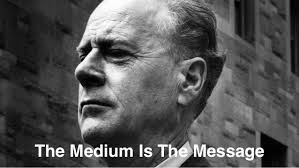

In the 1960s, Marshall McLuhan emphasized the value of message and the medium the message uses over its creator. This idea flies in the face of the modern era’s printed book as the ultimate expression of the writer, who toiled in glorified isolation as the big publishing house distributed it magically across the universe. McLuhan went on to predict a wireless world, where all messages are accessed instantly to and from a collective brain–what we now call mobile media.

Ever since authors shed the fantasy of a big publishing house model, many midlist and novice writers have opted to write speculative books delivered to reading tablets–print on demand–once they realized that they had the distinct advantage of having a product they solely owned that could be bought directly online. Now writers manage not only all creative decisions but also their own metadata, including ISBN number and price.

The most successful among them, “Fifty Shades of Grey” author E.L. James, strategized with aggressive genre mastery. She identified and directly engaged with present and future readers in social media hangouts. She insured that the upload to Amazon, iBookstore, Barnes & Noble, Kobo and Sony Reader could truly pay off. Big publishing houses had long overlooked such popular fiction genres as romance and science fiction. Now big houses along with the public (and movie studios), scout for bestselling indie authors.

Which prompts the question: what can screenwriters learn from this?

Flashback: Hollywood, circa 2001. Gutenberg almost left the building. Talent agencies began to scan screenplays into computers, making obsolete their script library (that also served production and casting). This was first done in the name of efficiency to save storage space. Printed copies went out as usual, delivered by hand. Then, after reliable email attachments came into general use, clients’ revised drafts could be distributed with an easy click.

But issues of control arose when it came to spec scripts. Reverting to type, the market marched backwards by sending sealed hard copies to buyers’ homes after hours and/or watermarking screenplays (so that pirated copies could be traced to a leaker) to accommodate time-sensitive, high stakes spec submissions. No thanks to the collective brain, many scripts were negatively profiled on the net via the tracking boards, and dismissed almost immediately. Though the market was fading, specs still held strong as an essential career strategy.

Truth is, the shark, like Oprah’s couch, had been thoroughly jumped. Around 2008, a certain major studio dropped the compulsory rain or shine weekend read. I recall a stunned colleague announcing at a staff meeting, “They’ve decided from now on to be more selective.” It never occurred to anyone to heed McLuhan’s prediction of electronic (vs. physical) delivery as its own high-impact message by posting a script on a private site with a password. Or trying the unheard of idea of posting a property MLS style with specs and stats that a prospective buyer’s gut could go with or without. First launched in email in 2004 as a free annual development survey, Franklin Leonard’s The Black List now offers a gated community tour for producers, directors and executives eager to identify the status of popular scripts idling in studio development or possibly overlooked (or looked over) gems.

A few weeks ago, the WGAW sanctioned use of the site solely devoted to promoting professional screenwriters’ work, searchable not only by name and title but by detailed genre, logline, budget and attachments as well as rated by reviewers. In the shadow of crashing tentpoles, opportunity has never knocked louder. Yet, how often have screenwriters solely described their work as a “calling card” that speaks for itself? By insisting on a virtual blind taste test, the writer’s identity elicits little more detail than a name followed by the question of who their agent is. Without a game a name is just a name.

Contrast that with what happens when a book is enthusiastically recommended to anyone. The question of “who wrote it?” paints a creative persona with details about gender, race, nationality, childhood, life story, life span, regional experience, class, politics. Expressed appreciation might extend to the book’s authentic atmosphere crafted by a mastery of language, character, genre cred, ear for dialogue, and clarity of message that all together earn that writer the reputation for ability to dial directly into universal truths.

Any kind of writer — dead and buried — or alive and writing, can “like” McLuhan, “friend” Gutenberg and become easy to discover via personal websites, genre driven blogs, mashup videos and show up on you-name-it social media to attract not only readers but loyal admirers. Why not screenwriters?