On Landing My First Job in the Business on Martin Scorsese’s ‘Mean Streets’

10 pm. NYU Film School, The East Building 8th floor, Editing Room.

“Who wants to work on a movie?” a voice pitched, over the din of old time moviolas. We worked on the same ultra durable film sewing machine used by all the studios in their heyday. (It now occurs to me that maybe these are what inspired “Star Wars Episode V’”s AT Walkers.) We used a form of scotch tape to make temp edits, and carefully scraped the tape with razor blades to carve the film sprocket holes, a frustrating and messy business. Hours melted away. Time stood still.

Every wannabe filmmaker in the editing bay just wanted to finish and be done. “I need two camera assistants… a gaffer and…a script girl,” announced the voice I now recognized as Mitchell, our TA. Groans were heard. “OK, there’s coffee in it, on me,” definitely sounding like Mitchell. Heads poked out. Five guys plus me, the only girl around, threw on our coats and shuffled past the purple walls trimmed with bright yellow paint, yawning and stretching. We piled into a station wagon parked in a red zone.

I asked, “Is this your car?”

“No,” Mitchell answered, “It belongs to the bank, it’s a lease car.”

“What’s a lease car?,” I wondered.

Around eleven, we pulled in front of the Gramercy Park Hotel, a seedy place in those days. The lobby couldn’t have been creepier. But the elevator, an old fashioned cage, was. It occurred to me as we were being yanked up a few flights, that maybe I‘d made a mistake. The cage opened onto a fairly well lit hallway. But that wasn’t a good thing. A door opened and light spilled out like the sun just came up. Guys were pacing around as far as the phone chords would take them. Things settled down, however, when the eye of the storm, a dynamo with shoulder length black hair and a dark but smiling countenance, became the center of attention.

“Mitchell! So, are these the kids?”

“Yeah, Marty,” said Mitchell, who then pointed out two camera assistants, two gaffers and me, whom he called, “the script girl.” Marty stared at me and said, “This girl? She’s… tall. I mean look at her. Look at me…. Look at her.” Just as directed, the entire room fell silent, looking at me. Marty threw up his hands, shaking his head. With that, he left the room. I felt my feet move to follow him to another part of the suite, where someone was on the phone with “the coast.” Then it hit me that all these people were here from California, a place I’d never been. All around were sketches of scenes from the film they were making. Marty sat down at a nearby desk. Instinctively I sat down and said, “I don’t have to be tall.”

He grinned and said, “that’s good.” He showed me some of his sketches. They were very specific. He explained how he wanted the continuity notes to be, since he’d be referring to them in the editing room in California.

“So, you think you can do this?” he asked.

“Yes, I can,” I nodded.

Then we both stood up. The disparity in our heights threw him again. “Okay,” he said, sounding as if inspiration had just struck. He threw his shoulders forward as if to model a dance move or do a James Cagney imitation. Instinctively I followed his lead. I gently hunched in his direction. He beamed, “Yeah, that’s good.”

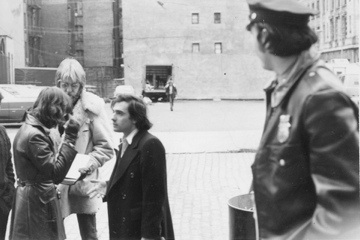

We spent the next ten days strategically focused like our lives depended on it. Rest was something the rest of the world did. We filmed in Little Italy, one step ahead of the teamsters, since we were a non-union shoot. The local cops watched out for us. One night, Marty’s mom, Catherine, acted in a scene. A restaurant in Marty’s old neighborhood opened its doors at 3am and treated us to the meal of our lives.

Marty was patient and kind. Only once did I truly fuck up. In one scene Robert De Niro was holding a gun. In the middle of shooting he switched hands. I shouted in a panic, “The gun needs to be in your other hand!” Needless to say, I made the man angry. De Niro stepped out of the scene. He walked up to me. “Please don’t do that,” he said in that soft voice that made you feel you had his complete attention and you wondered if maybe that wasn’t a good thing. Then he walked back into the scene, as though nothing had happened.

On our last day, we were shooting at night in an old cemetery, a stone’s throw from an apartment building where a party scene was being staged above us. This was an exterior pick up shot of the action inside through the window. I got to stretch out and rest. Earlier in the evening the crew had given me flowers because it was my birthday. I plopped onto the cold ground, leaned up against one of the thin granite tombstones with the flowers, my shooting script now fat with notes to Marty, my stop watch around my neck, looked up at the moon and thought, “So this is the film business. Wonder if anyone will ever see his little movie.” The rest, as they say, is history.