How Kathryn Bigelow & Eric Red Gamed the System to Launch Their Careers

Kathryn Bigelow and Eric Red not only delivered an exceptional screenplay to their agents, but along with it, equipped us with a real world plan of attack. This made “Near Dark” an exceptional setup. I was head of Gersh’s Literary department, itching to sherpa my clients up Everest. Kathryn and Eric’s tactical scenario offered the kind of dynamic activism agents live for.

We didn’t have a big meeting or even work out details over a fancy meal. Kathryn and Eric’s determination to overcome conventional industry-wide resistance to anyone outside the insider directing pool was palpable. When I signed Kathryn, I could see she was someone who was determined to not only even the odds against her achieving her goal – but not by kneejerk jumping at a single opportunity. Instead she was prepared to exercise discerning conduct aimed to promote a long and productive career. She was very smart to understand the difference, which led to sometime in 1986, when Kathryn and her writer/director friend Eric Red, whom Melinda Jason represented, made a pact.

Melinda had her own literary agency, but in many ways, she was my mentor. She’d gotten her start in the industry in the legal department at Fox features doing personal service contracts right after getting her law degree from USC. After a few years, she segued into becoming a literary agent. Over the course of working at a few mid-sized companies, she made a lot of friends who were agents. When she was able to start up her own company, she kept those friendships even though her friends were also her competitors. She knew there was a bigger, badder enemy out there we needed to protect each other from, by sharing information and sometimes, clients.

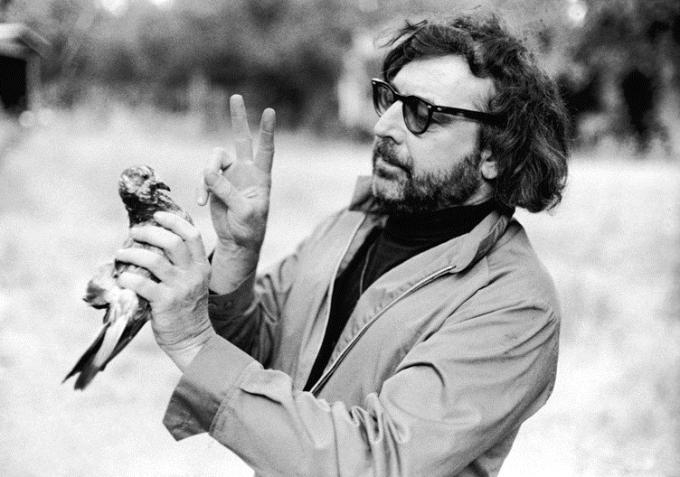

She reasoned that as independents there was safety in numbers to neutralize the predatory practices of corporation-sized companies – both agencies and studios. She also knew there was enough to go around for everyone. Perhaps it was because she’d grown up in a family with deep roots in the golden age of the entertainment business — her uncle directed “Rebel Without A Cause” and before that, her great uncle was president of the Directors Guild, having directed “Top Hat” and many other Astaire films — that fueled her positive expectations.READ MORE